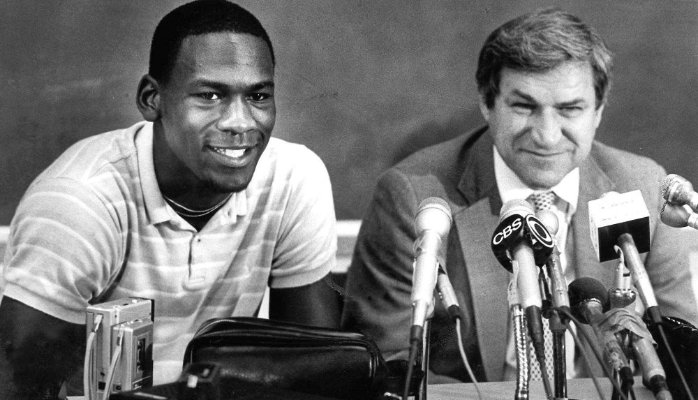

A management genius shuffled off this mortal coil this past weekend. Trouble is, we all mistook him for a basketball coach.

In 1961, a little-known assistant coach named Dean Smith took over as leader of the University of North Carolina basketball program. In his 36 years as the Tar Heels’ head coach, he won two national titles, won at least 20 games for 27 consecutive seasons, and became the architect for one of the top five college basketball programs of all time. His achievements as a coach make him a giant in the world of basketball… but it turns out he was also a damn good manager.

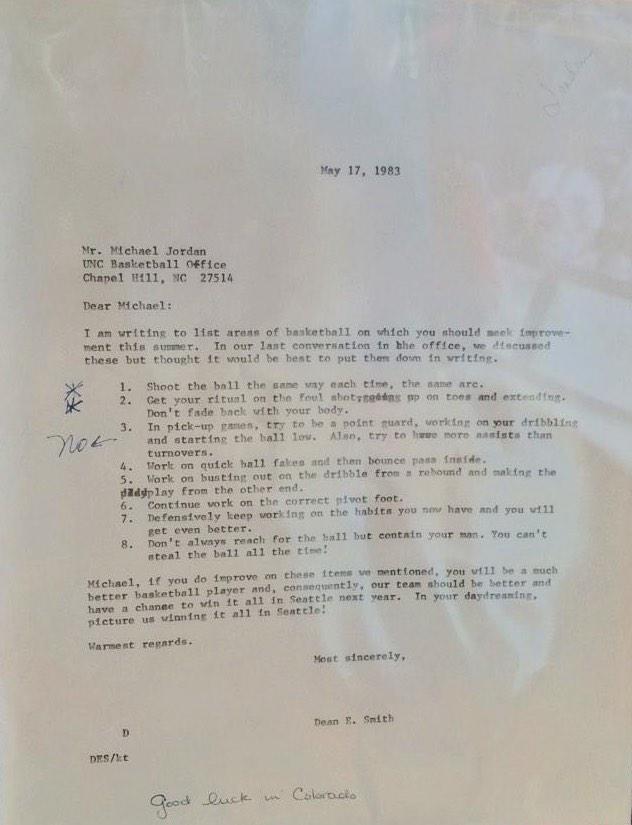

In the aftermath of his passing, NBC and Yahoo Sports have surfaced a letter written by the already-great Smith in 1983 to a promising, yet skinny, freshman on his team. One Michael Jordan received this concise assessment of areas where improvement was needed (click image for full size):

In short, Coach Smith puts on an absolute clinic on giving performance reviews. Let’s break this one down:

1. This is a review full of respect. One of the greats in the game just called this skinny 18-year-old “Mr. Michael Jordan.” A small signal, but one that shows the way. We’re less formal in this day and age, but respect that rolls downhill never loses momentum.

2. Coach gave the review in person. This letter is a follow-up. This wasn’t a hearts-and-flowers retrospective, just a senior manager who knows what he’s doing giving face-to-face advice to one of the new kids. It comes from relationship.

3. The review is specific. If you’re not conversant in basketball-speak, just know that Coach Smith is speaking to fundamental skillsets upon which the rising sophomore can improve. This is a list of things to practice. There’s no ambiguity on what this kid needs to work on to get better.

4. The review is concise. One page, typewritten, less than a couple of hundred words, and a hell of a lot more instructional than this much longer post.

5. Coach Smith signals the importance of individual and team. Here, the management guru motivates change and improvement (“If you do these things”) by describing greater individual success (“You will be a much better basketball player”) and the impact on the team (“…and, consequently, our team should be better and have a chance to win it all.”).

6. It ends with a positive vision. “In your daydreaming, picture us winning it all in Seattle (the site of the 1984 NCAA championship game)”. Envisioning has emerged as a key component of mental preparation for athletes in all sports, and Smith was one of the first to teach his team how to unlock the power of seeing the success first.

If every performance review contained these elements, would we live in a better world? I say yes.

I will, with GREAT trepidation, offer one criticism of Coach Smith’s letter. There was no mention of the year’s successes. As a freshman, Michael had only just MADE THE GAME WINNING SHOT TO WIN THE NATIONAL TITLE for UNC and had been named the Atlantic Coast Conference’s Freshman Player of the Year. And that “good luck in Colorado” note at the end? Michael had made the USA Men’s National Team and was on his way to summer practice. He would lead the team in scoring and win Olympic gold in 1984, and presumably would have worked out that thing about “shoot(ing) the ball the same way every time”. So there might be a couple of things to celebrate in there.

On the other hand, it’s not hard to guess that, perhaps, it was Coach Smith’s commitment to always improving, always looking forward, and never resting on his laurels that made him great. And, perhaps, those values helped give that skinny kid a sense of focus and desire to improve.

And, by the way, that skinny kid eventually became the best basketball player of all time.

Excuse me, I’m headed off to thank a mentor for my last tough-yet-accurate review.